Dear English speaking readers,

up to here is what we have in English of this Blog on Group Analysis

in memory of the Life and Work of Juan Campos

What follows are some more ideas with which for the moment we put suspension points…

EPILOGUE

Mercè, Pere and Hanne… for over three years now we have been elaborating this Blog in our small group of three —with the invaluable collaboration of the obliging family of Mercè— unravelling the threads which connect this group work carried out on the side of Juan, but also with the participation of colleagues who generously pitched in on the projects we proposed… and who, without doubt, are always invited to contribute their memories, points of view and trajectories. For the moment, the threads follow the development of this group of analysis of long gestation since the seventies of last century and presented in public in Barcelona in January of 1989. They maintain their tension through the fundamental question about change, about social change and individual change, what we would like, should and could change between all; a subject which comes and goes over the years and which is particularly pinpointed in this Blog in relation to groupanalysis in a last project of 2008. Here we order chronologies and subjects. The shared history contains and links the different projects on their way towards this horizon of change ever more beyond. The Blog also embodies the links between the plexus of Juan, Pere, Mercè and mine. There is the analysis transmitted with special clarity by Juan and Pere, groupanalysis as a way of living by Mercè and my systemic analysis of institutions and their possibilities of change. But this would be my reading and I don’t want to sustain any exemplary position, although I take the risk of pointing out some advances that have been made, particularly during the last stage of our experiences. However, all these are questions which every reader can discover and formulate in his own way.

Having arrived at these suspension points of the Blog, I would like to share some reflections in relation to the frames of reference for thinking and implementing the change in the fields of knowledge and of experience. The first, as if a circle was closing, an issue dealt with by Thomas S. Kuhn in his essay The structure of scientific revolutions[1] . In the sixties this was an epoch making book. Juan Campos, following his intuition of investigator “found” it, studied it and underlined it line by line at a moment he started to be interested in an educational reform for health professionals. In his historical inquiries, Kuhn discovers that the revolutionary changes, when they occur, are changes of paradigm[2] of the science in question. The changes are not produced through accumulation in the theoretical and practical development of a science, although this also. However, the paradigmatic changes are of a different order and are produced for reasons independent of ‘normal’ conceptual, theoretical, instrumental and methodological development of the sciences, although the changes in the latter can articulate themselves with the first. These discoveries pose an alternative point of view of scientific advance and change the image we had and still have of science. Says the author: Perhaps we should abandon the explicit or implicit idea that the change of paradigm brings the scientists and those who learn from them more and more towards the truth. We are too used to see science like an enterprise which constantly brings us nearer to an objective predetermined by nature —Does a “true” science of nature exist?, jots down Juan on the margin. But, asks Kuhn, has there to be such an objective? Can we not explain science itself as well as its successes in terms of the development of the state of knowledge of a community at a given moment? And he suggests: If we could learn to substitute ‘evolution of what we know’ for ‘evolution towards what we would like to know’, perhaps a series of problems which are now most pressing would then disappear.

The essay of Kuhn left its imprint in the intellectuality of that epoch but the absence of subsequent significative resonances makes one think that the general response of the scientific community was the habitual one in front of novelties and the insinuation of radical changes: i.e. an active and passive silence. It was precisely this one of the many discoveries of Kuhn when investigating the phenomenon of change in science. Chapter XI of the essay is titled The Invisibility of Revolutions, annotated by Juan as Techniques of effective Science Pedagogy.[3] In this chapter Kuhn deals with the more than complex problem produced in the transmission of science by the evolutionally inseparable link between the written text, and the innumerable phenomena —denial, abolition, silence, distortion, misinterpretation, etc.— which inter alias lead towards a cumulative idea of a determined science or science in general.

Kuhn in different chapters addresses not only how discoveries and proposals of change are silenced, but he shows us in his historical analyses that part of the attitude of the scientists is not to expect novelties or unexpected results, and when these do appear they are interpreted as failures of the scientists or of his instruments. Neither is it a part of the objectives of ‘normal’ science to elicit new phenomena or invent new theories and the scientists tend to be intolerant with the colleagues who invent them. We can add that a paradigm in science means that there is a solution and this security at times and to a certain point converts the activity of investigating in an activity of a puzzle in which the puzzle itself does not have intrinsic value, an activity that even can arrive to isolate a scientific community from socially important problems because these cannot be posed in terms of the puzzle.

But, as is known, what most interested Juan Campos has to do with the elements which condition teaching, learning and training professionals. And, the various colours with which he underlined the text are a sign of multiple readings and that Kuhn in this he made him see clear. Scientists never learn concepts, laws or theories in abstract but always linked with applications and ways of solving problems. These intellectual instruments from the beginning are inserted in a pedagogically previous historical unit which presents them with and through its applications. A new theory always is announced in the context of ‘natural’ phenomena without which it would not even be a candidate to being accepted. Science illustrates the generalization that truth and falseness are in a unique and unequivocal manner determined by confrontation of statements and facts. The way how pedagogy of science entangles the discussion on theory with commentaries on its application only reinforces this “confirmation-theory”. The person who reads a scientific text easily takes the application as evidence of the theory. But a student accepts the theory because of the authority of his professor and text, not for evidence. The application which comes with the text is not presented as evidence but because learning the application the student learns the paradigms which are the basis of praxis. However, there are instances when a new theory breaks with the tradition of scientific practice, introducing new rules and a different universe of discourse. This only occurs when the old tradition has very much gone astray and a crisis is produced that brings with it its own questions, as could be: What is extraordinary investigation? How is the law of anomaly made? How do scientists proceed when they realize that something has gone terribly wrong, circumstances for which their training has not equipped them to manage? These are questions[4] that Kuhn deals with in chapter VIII on Response to Crisis. He considers that these are questions that need to be investigated and require the competence of the psychologist more even than the one of the historian, because what intervenes between the first sensation of the problem and the recognition of an alternative at hand, must be in great part unconscious.

Kuhn’s text merits being a compulsory subject in all careers and professions. The use of paradigm for conceptualizing change is recent and its utility in all scientific fields seems assured however little we venture into the subject. What we bring here to the dialogue is its use in posing urgent questions of communication and communal living which concern humanity and the human groups, and the long way we still have to go in clarifying and solving these questions.

My second reflections on change bring me to the present. They refer to the frequent fact of identical o complementary changes that emerge at the same time in different fields of investigation, in this case, and once again, history and group analysis. Concretely I refer to the study of a historian[5] of social changes in Europe and Occident this last half century. This historian makes us feel “at home”, he talks about us, the groups in which we move, the differences we have difficulties in reconciling and the consensus that we want to achieve so badly. As a good historian, he talks in the name of a group of groups in which the groupanalysts are one more. I feel that the languages used meet each other, they overlap with one another, at times they differentiate themselves, but they always look for communication and comprehension of what sometimes does not seem comprehensible. I permit myself to quote freely because of identification with what is said in relation to the world we share.

Politically, our epoch is one of pygmies; however, this is all we have. The author ignores how much of “pygmies” we feel ourselves on publishing this Blog. But this must not be an excuse for not searching and finding the place and the moment for saying what we think and what we do.

The readiness for being in disagreement, rejection and unconformity constitute the life-blood of an open society. We need people who make a virtue of opposing the opinion of the majority. In recent decades disconformity has been closely related to the intellectuals. Unfortunately, the contemporary intellectuals have shown little serious interest in key aspects of public questions. If anything can be read in this Blog, and more so the people who knew him, it is that Juan Campos has shown always and freely his disconformity when it seemed to him. It is not that one would consider him an intellectual, at least not in the habitual sense of the word. Before even a groupanalyst, Juan always has been an investigator, a scientist, a physician. For sure, he did not make a virtue of his opposition to the opinion of the majority when he expressed it, but the denial and silence have “massified” the resistance towards his proposals and in this way have highlighted the disconformity he frequently manifested, always within the law— something what cannot always be said of the ones who tried to silence him— when necessary proposing and promoting the change of law.

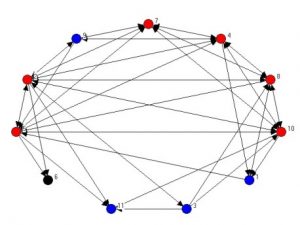

On the other hand, it is not so much a question of being in accordance or not, but it is a question of how we debate our common interests. To renovate our public conversation seems the only realistic way to bring about a change. With surrogate debates on identity or the criteria of belonging to such and such a guild, we will find that these not only do not further the expression of opinion but suppress the latter together with its possible expression. We will not think in another way if we don’t talk in another way. At the beginning was the word… The successive workshops[6] organized by Grup d’Análisi represent a continuous effort to bring surrogate debates to become transformative dialogue in form as well as content and objective. Perhaps the most creative contribution as far as a renovation of public conversation is concerned is the one proposed in the scheme of the three cultures of Pat de Maré[7] —Bioculture, Socioculture and Ethic-Koinonic Culture[8] — and which not only introduces the idea of a language of a different analysis for every culture but which integrates the conscious and unconscious levels of communication. The whole scheme links into the dialogue as the place of access to the different languages, in fact to all possible languages, where the common interests are debated with maximum knowledge of cause and most possibility of change. In principle dialogue is the place of divergence as well as of integration where, according to the author of the scheme, “we learn to talk with one another” and, according to our investigations, for this to be possible we have to provide groups of different kinds and sizes relatively stable of individuals who meet regularly and continuously to discuss critically shared problems and explicit coherent alternatives and ethics of everyone individually and the group in particular.

On one hand, the critique of the systems and the changes that would be necessary, have been in the air for decades. It should by now be clear that the reason why they have not occurred or they don’t function is because they are put into practice by the same people already involved in the dilemma and the conflicts. In this sense the group of analysis suggests to promote “an operative groupanalysis in which the process of analytic understanding, explanation and comprehension have the objective of operating on these same processes in a way that explanation and comprehension could change and in fact do change through the development of a convergent epistemology and methodology”.

It seems obvious: There is no room anymore for the great narrative, the exhaustive theory in which any and everything can be included. The development of groupanalysis as a methodology confirms this declaration. Perhaps now we are more conscious of that we are to make do with what we have, without such an all inclusive narrative. Neither can we rediscover the kingdom of faith as it had been conceived before. But this situation should not hide from us the importance of morality in human affairs. Even if we admit that life has no higher purpose, it is necessary that we assign to our acts a meaning which transcends them. We need a language of purpose and aims. It is not necessary that we believe that our objectives have a good chance of being achieved. But we do need to make our objectives explicit and the alternatives to achieve them in a sufficiently clear manner so as to have faith in our decisions and elections during the process that leads to the next point of evaluation. A group of analysis would be the operative base of the projects which assures the alternation between face-to-face and virtual groups, between dialogue and written elaboration, between small groups and larger groups, this is to say the alternation between methodologies that contribute different points of view to the questions under debate. If we really make ourselves this proposal, an articulation and complementarity in view of the changes we want to achieve has to be possible.

Epilogue… Why on earth has it occurred to me to write an epilogue? This Blog is an epilogue! Wikipedia inter alias: evidence of all that serves as the basis of conclusion. It would seem that just as there doesn’t exist the theory, neither there exists the conclusion. Although we may not be here, there will be others who follow the path of life, of conscience —to know together, as Juan would say—, of thought, of feeling… Let us hope. Anyhow, one of the definitions makes me smile: epilogue, a rest offered to the activity of imagination and feeling[9]… Well, let’s have a break, let us rest for a little while, it will do us good…

But, since thinking does not seem to permit a rest, I shall finish in the present. This morning, as I read La Contra of the Vanguardia (back cover of the newspaper), where everybody says their thing, where I feel like a companion of this strange journey which is life, this morning a Woody Flowers[10] said:… but face-to-face education will go on being the motor of personal and social progress. Why? Because the important thing is not the content but how to teach to learn, to learn how to learn, one comprehends better and more rapidly in a personal relationship… the capacity to learn and to improve as a person depends on the face-to-face team work…

Groups ahoy!

[1] Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago IL: The University of Chicago Press.

[2] The paradigm —an appropriation of the concept by Kuhn— of a science has two essential characteristics: 1. It assures that the achievements of a science are sufficiently original, without precedents, so as to attract a permanent group of adherents from other scientific activities in competition. 2. This scientific field should be sufficiently open as to offer resolution of all types of problems to professionals who just redefined themselves. When the paradigm stops to fulfil this function, the science and the scientists enter in crisis and times of change of paradigm are near. However, the change of paradigm will not happen until there appears a new paradigm that could take its place. To reject a paradigm means that there is another better one to pose the pressing problems and possible solutions.

It is important to point out that the paradigmatic changes relate to what happens between groups that adhere an old paradigm, or to a new one. This is the point which interests Juan and which he comments and underlines to the last moment: “When we speak of the life and work of Trigant Burrow and S. H. Foulkes, we are speaking of the ‘creative process’ implicit in the revolutionary change which was necessary to give to the individual method of analysis of Freud in view of discovering in different moments and each one on his own the Group Analysis… Underlined and annotated in 2008 the following manuscript commentary: “This idea seems to me fundamental and should be posed in group not only from the personal point of view, but from the socio-political and cultural point of view!

[3] Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago IL: The University of Chicago Press.

[4] In an attempt to clarify these questions, there are many contributions of Juan Campos in moments of crisis of the associative groups to which he belonged.

[5] The reader will find all these references in chapter 5: What do you do? of Judt, T. (2010). Ill Fares the Land . London: Penguin Press.

[6] “Metamorfosis de Narciso: Identidad grupal o cultura grupal”; “Del psicoanálisis al grupoanálisis: El difícil camino hacia una cultura grupal”

[7] Campos, H. (1986). Group Theories as con-text of group psychotherapy in particular and of group work in general.

[8] For Pat de Maré, Koinonia has to do with a drive development radically different to the one of libido, not finishing in love but in friendship. It is a gradual transformation, through dialogue, of mutual hate generated in the group into impersonal fellowship of Koinonia. The Ethic-Koinonic culture functions on the base of what the author calls “humanized logos”, the principle of meaning, which represents an ethic-cultural jumping board from where to observe the three cultures.

[9] The ancients used the epilogue for producing the effect which is expected in the theatres of actuality, of the sainetes, represented after a tragedy or a drama, as to calm down the violent impressions the piece had awakened. It was a type of a rest offered the activity of the imagination and the sentiment.

[10] Engineer and professor at MIT, promoter of FIRST (For inspiration, Recognition, Science and Technology) and many other enterprises of education on-line.